Lara Costafreda was born in Llardecans, Catalonia. She studied fashion and plastic arts at BAU (Barcelona), Central Saint Martins (London) and PUC-Rio (Brazil). In addition, she has a postgraduate degree in Creative Illustration and visual communication at the University of design EINA (Barcelona). Her technique includes various materials such as illustration, watercolor, oil and recently he has moved to large format work: muralism.

She combines her work as an illustrator and creative director of different magazines and international brands with teaching at various Catalan universities. At the same time, she is involved in social impact projects linked to the culture of peace, social justice and immigration as an artistic activist in the campaign “Volem acollir” (Casa nostra casa vostra), the clothing brand of the ambulant sellers of Barcelona Top Manta or the campaign of art, education and culture of the school of Llardecans (Lleida) to stop rural depopulation.

Her work and testimony have gained international recognition, reaching countries around the world such as: Chile, Mexico, Argentina, United Kingdom, China, France and Japan, among others.

Your work has a direct relationship with ecology, which we could define as a love letter to nature. What made you decide to work around this thematic line?

I grew up in a rural environment, with direct contact with nature and the outdoors. It is an inherent link of which I was not aware until I went to study design in Rio de Janeiro when I was 22 years old. It was then that I began to paint elements linked to nature, of Brazil and the Mediterranean. It was not a deliberate chosen style; it came very naturally and even today it is one of the themes that I like to illustrate the most.

You are a multidisciplinary artist who works with a wide range of techniques and media. What are the artistic and conceptual references that have influenced your work?

I don’t have very specific references, there are many things that I like or that influence me aesthetically as well as conceptually. Normally, I keep them in folders that I review every time I start a work. My work process always starts with a moodboard; a collage of images that define the visual universe that I will work in that project. These images come from my archive, but mostly from the search I do specifically for each project. It’s a part of the process that I really enjoy.

You combine your work as an artist with teaching at universities such as BAU, LCI and Ramon Llull, in Barcelona. What do you think is the state of art education today? What virtues and weaknesses do you find?

I studied fashion design at a university that had a very conceptual and experimental educational line. We spent four years reviewing references that are closer to contemporary art and social criticism than to the closet of any person in Barcelona. The career taught me a working methodology that I keep as a treasure and that has helped me in countless things in life, both professionally and in the field of activism.

When I finished my degree, I got a reality check, which caused so much frustration among my colleagues. All that we had learned did not help us to work as a designer for Inditex, which was what we could aspire to if we did not stay in Barcelona. We had not been trained for commercial fashion design, nor were we prepared for the companies, nor for unbridled consumerism, nor for fierce capitalism.

At that moment we collectively complained about this fact: “how can it be that after four years of study we are not prepared for the working world? This question is the main insight that challenges teachers and educational institutions around the world every day. Is the ultimate purpose of education to serve a productive system? Does it teach us to live better education?

As a teacher I have seen how many universities have changed their model to provide an answer to the above question. Most of the universities I know do capitalist training; they teach students to develop the world of work so that when they leave, they can access the market and start producing quickly. If you look at it coldly, the student pays thousands of euros to make sure they have access to a working position when they finish. This is how the educational models we know work.

As Marina Garcés says in her book Escola d’aprenents:

“we humans are the ones who have to learn everything and never learn anything. This is the tragedy of education (…) What makes us human is having to be educated in order to be. And what makes us human is that no educational system ensures that we learn anything important that will make us better. The history of mankind stages this tragedy: it is a long chain of learning and an even heavier chain of mistakes. We accumulate as much knowledge as incomprehension, as many inventions as disorientation”

In addition to your work as a designer, illustrator and creative director, you are involved in different social projects, such as Top Manta, the Barcelona Street vendors’ union. How is this activist side represented in your work? Have you ever turned down a collaboration or commission for not following your loyal values?

As a communications professional, I constantly live around marketing strategies and plans to sell things. One day I thought that all that knowledge could be at the service of people and projects that work to make the world a place where everyone can live with dignity.

Under this premise, in 2016 I co-launched, together with many other colleagues from the world of communication and activism, the campaign “We want to welcome” and the entity “Our house is your house”, which over the years has become a space from which we accompany transformative social projects and initiatives. We collaborate with many incredible groups that do a super necessary task and we do it from the economic altruism because we understand that society needs us to be able to create alternatives that help us to live better without expecting an economic reward in exchange.

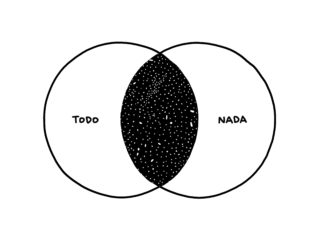

This is in constant contradiction with everything in life, not only in my work. We live in a deeply individualistic world where everything is driven by money, recognition and power. It is impossible to escape 100% from this wheel because the bills must be paid at the end of the month. But even so, it is still important to be aware of it and try to change it.

Being conscious can be painful because you see all the violence in the world on a platter in front of you and you recognize yourself as a participant in it, but at the same time, consciousness is the only state of mind capable of imagining things differently, catapulting change and transforming society.

I work for whoever offers me a proposal and that always has contradictions. I say no to many things, especially those related to banks, since they invest a lot in art, culture and education, being these the most recurrent that usually come to me. But even though I am very lucky, and I can choose a lot, all projects come with a contradiction under the arm.

Over time I’ve learned that we usually can’t decide where the money comes from, but we can decide where we put it. And I try to invest it in those people and those initiatives that work to make a fairer world; I buy in cooperatives and projects of responsible, ecological and proximity consumption. Just as I invest my free time putting my knowledge in communication next to social demands, I donate money when I can and try to generate a positive impact on what I can. I don’t always succeed, of course, but I work hard at it.

Your illustrations have become famous all over the world, but above all they have had a lot of repercussion in Asia. You have had the opportunity to make a presentation of your work in Shanghai, how is it to work with people who have a culture so different from yours? What aspects should you consider when presenting a project in China?

It all started by chance. An acquaintance of mine works in a fashion company and called me one day to ask me a favor. She had invited a group of Chinese journalists to Barcelona bored of the typical tourist tours they asked her to visit small workshops of creators and creators of the city. In half an hour I had 30 journalists and a representative of a Chinese shoe company in my studio. They made me a very curious interview and left. The next day I was asked to illustrate the new campaign of the shoe brand and a month later I was in Shanghai presenting it.

That experience connected me with many people who kept proposing projects to me. Currently there is an agency that represents my work in China and before Covid19 I had gone a couple of times to present projects.

About cultural differences I would say that working for cultures different from ours is always a learning experience, but in this type of projects there are almost no transcendental differences. Advertising agencies work the same all over the world.

You have ventured into the world of large format muralism, and one of the works you have done in this sector has been a large format mural in the neighborhood of La Florida in Hospitalet del Llobregat. This intervention is part of the Pla Integral Les Planes Blocs la Florida and arose from a participatory session with children and young people of Esplai La Florida. How was the experience when executing a mural during a participatory process?

Very satisfactory, especially for the ease with which the Rebobinart team managed the production and execution of the mural.

Most of the large format murals I have done so far are printed on wallpaper because the clients asked for an illustration technique (watercolor) that would have been very difficult to do live on the wall.

A couple of years ago I painted the 700m2 of the rural school where I studied since I was a child with my brother, Titilamel, who is also dedicated to illustration, and even though I did a master’s degree that helped me to face the mural projects I have done, I have learned a lot with Rebobinart.